A summer frolic between young cousins changes to winter play without fanfare. The young actors and stage are constants. But key scenery changes unlock the passage of time — green grass fades to yellow, a young girl and boy trade lawn cotton costumes for blue winter coats.

In my youth, the stage for Sunday afternoons was always Granny’s front yard and porch. Old fashioned games of hide and seek, Easter egg hunts were all held there. I can recall many baseball games held there too that divided our large family in two. Granddad always played and all the kids and their spouses. Trees subbed as running bases while appropriately, home base rested near the steps of Granny’s front porch.

The preliminaries involved Southern scratch cooking at its best. But we grand-kids never lingered over our plates. Without guilt of leaving food behind, we’d rush out the side screen door to play. I imagine that cold February day caught on film was no exception. That day we were celebrating my young aunt’s birthday. Seven years older than I, my aunt is closer in age to me and the other grandkids than to our parents, her brothers and sisters. Was Jane turning eleven or twelve that day? I can’t really say. I’d guess the year as 1959, judging by my own appearance — with hair tied back in a pony tail, wearing that blue coat over a standard home-made dress, I look to be no more than four.

Much like the young girl I was, the camera buzzes around the action without ever landing. In its greed to capture the big picture for posterity, the action blurs; most subjects are in and out of the frame before eyes can discern their presence. It doesn’t help that images of vintage film grow faint, that they go gray and grow lines with age. Was that cousin Mike? Or Pat? I can’t really tell. It all goes too fast.

What I know for sure is that my Aunt Jane had just received a brand new bike for her birthday. Her first bike, because times and finances were tough for Granny and Granddad. And for some reason — I don’t know why — my young father was teaching Jane to ride her bike, while my mother captured the event on film. Who bought the bike for Jane? Was it my parents? Was it a joint gift from the family? I don’t really know — these details were not important to me then.

The rolling images of vintage home movies cannot tell a story alone. Spliced together without conscious editing, scenes require narration from one who lived through the event. Preferably the storyteller is one who can recall vivid details since it’s details that make stories come alive.

That’s why it helps to focus in on smaller pictures. In our story telling, it helps to content ourselves with telling little slices of life in great detail. Come in late. Leave early. Don’t over stay our welcome.

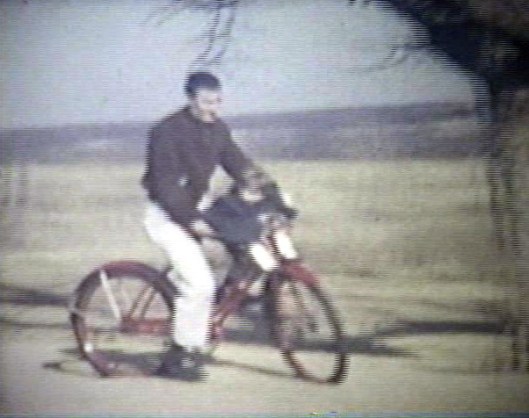

So here’s one smaller picture from that home movie where I hit the pause button: My young father balancing me on the handlebars of my young aunt’s brand new bike.

The handle bars are cold and hard. The grass makes for a bumpy ride. But I don’t care. I’m happy to take a spin with my father on my aunt’s new bike. I always found Daddy handsome — it’s a shame he didn’t learn this until lying on his deathbed. I hope he found the information “better late than never;’ I was just glad to remember to tell it.

But what I didn’t remember were times like this, when Daddy was nothing more that a big playmate. Surely with a child’s wisdom, I knew this fifty years ago, before Father Time dinged up my memories.

This then, is how I wish to remember Dad: braving the February cold to play the hero, teaching us kids a few new tricks.

It happened during the great purge – the day we wiped the house clean of my parent’s lives.

It happened during the great purge – the day we wiped the house clean of my parent’s lives.